People

Philosophers

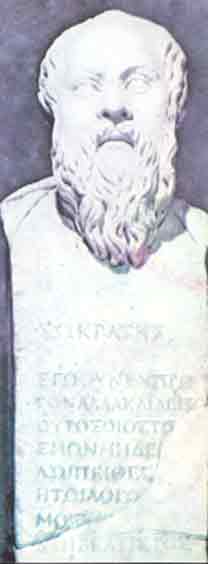

Socrates (469-399 B.C.)

Socrates {Sokratis ~ Σωκράτης} (469-399 B.C.). Greek philosopher of Athens [Place Names]. Famous for his view of philosophy as a pursuit proper and necessary to all intelligent men, he is one of the great examples of a man who lived by his principles even though they ultimately cost him his life.

Knowledge of the man and his teachings comes indirectly from certain dialogues of his disciple Plato [People] and from the Memorabilia of Xenophon. In spite of conflicting interpretations of his teachings, the accounts of these two writers are largely supplementary.

His most important contribution to Western thought is his method of enquiry, known as the method of elenchos ({elenhos ~ έλεγχος} = examination, inspection), which he largely applied to the examination of key moral concepts. For this, Socrates is customarily regarded as the father and fountainhead for ethics or moral philosophy, and hence philosophy in general.

Socrates' method of elenchos consists of questions and answers about the definitions or logoi ({logi ~ λόγοι} = reasons, definitions -- singular logos, {λόγος} = reason, definition), seeking to characterise the general characteristics shared by various particular instances. To the extent to which this method is designed to bring out definitions implicit in the interlocutors beliefs, or to help them further their understanding, it was called the method of maieutics ({ekmeefsis ~ εκμαίευσις} = aiding, or tending to, the definition and interpretation of thoughts or language). Aristotle [People] attributed to Socrates the discovery of the method of definition and induction, which he regarded as the essence of the scientific method. Oddly, however, Aristotle also claimed that this method is not suitable for ethics.

Socrates applied his method to the examination of the key moral concepts at the time, the virtues of piety, wisdom, temperance, courage, and justice. Such an examination challenged the implicit moral beliefs of the interlocutors, bringing out inadequacies and inconsistencies in their beliefs, and usually resulting in puzzlement known as aporia ({απορία} = puzzlement). In view of such inadequacies, Socrates himself professed his ignorance, but others still maintained their knowledge claim, whereby Socrates claimed that he being aware of his ignorance is wiser than those who, though ignorant, still claimed knowledge -- a claim which seems paradoxical at first glance. This claim was known by the anecdote of the Delphic oracular pronouncement that Socrates was the wisest of all men.

Socrates used this claim of wisdom as the basis of his moral exhortation. Accordingly, he claimed that the chief goodness consists in the caring of the soul concerned with truth and understanding, that "wealth does not bring goodness, but goodness brings wealth and every other blessing, both to the individual and to the state", and that "life without examination is not worth living". Socrates also argued that to be wronged is better than to do wrong.

Socrates (469-399 B.C.)

04-22-2004